|

DG: These days you mostly stay away from what you and many others have called the “po-biz.” In your conception, what precisely does the term embody? And why might younger poets, especially, be better off not immersing themselves in this world?

Dana Gioia: “Po-Biz” isn’t my term. It’s literary slang for the Creative Writing profession. I use it literally. There is a difference between poetry as an art and teaching poetry writing as an academic job. Art is the pursuit of the individual imagination. Creative writing is an institutional career, subject to all the compromises of professional employment.

Creative writing has become a business. Unfortunately, it’s now a low-growth one with poor outcomes for many participants.

DG: It would be interesting to hear your thoughts on narrative poetry. In Studying with Miss Bishop, you write: “My literary education had trained me to consider plotting an obvious and superficial device unworthy of serious attention. Plots were what the unenlightened noticed in literature. Showing too great an enthusiasm for the story line of a novel or long poem bordered on bad taste.” You have published many narrative poems. The first was a powerful longish poem, “The Room Upstairs.” Can you talk about the composition of that poem? What inspired you to do something so different from most other contemporary poetry?

Dana Gioia: Until the past century poetry was understood as a capacious art. One could write poetry in any of the major modes of literature—not only lyric, but narrative, dramatic, even didactic. When I was in college, however, I was quite explicitly told that contemporary poetry was limited to lyric expression. All of the other traditions were spent, defunct, exhausted.

I was puzzled why the champions of poetry professed such a diminished version of the art. In the general culture, people still told and acted out stories in every other media—from novels and movies to comic books and pop songs. People need stories to clarify their own existence. There are some truths that can only be expressed as stories.

Why couldn’t poetry tell stories? It made no sense. It seemed like a failure of imagination.

DG: Did studying with Robert Fitzgerald at Harvard help you transcend the so-called “standard” literary training of that time?

Dana Gioia: At Harvard I took a seminar from Robert Fitzgerald on narrative verse. We read Homer, Virgil, and Dante. I was impressed by how powerful these ancient poems were. I also saw how differently the poems told their stories as opposed to how they might have done the same in prose.

It is crucial for young poets to read old works. If you read only current writing, you are at the mercy of fads. You develop no perspective on what really matters. Let’s even use the terrible C-word—classics.

Great works from other ages and other languages are not only enjoyable and illuminating in themselves; they provide perspective on the assumptions of your own age. Otherwise you are a prisoner of your own historical moment. Most of the great Modernist innovators—not just Pound and Eliot but also H.D., Jeffers, and even Frost and Cummings—revived some lost primal element from ancient poetry. The Modernists used ancient things to make themselves new.

DG: Did Fitzgerald’s class spur you toward experimenting with narrative verse?

Dana Gioia: Fitzgerald’s class got me thinking about how I might write a contemporary narrative poem—not an epic but a sort of intensified short story in verse. I knew I couldn’t begin with something on the monumental scale of Dante’s Commedia. How could I tell a more compact and realistic story, a contemporary one, at a sort of middle length? I wanted a compelling narrative that would rise to the level of lyric poetry at key moments.

There were no useful models by living poets. The narrative poems I found were prosaic. So I went back—first one, then two generations. And there was Robert Frost at the very start of his career. I saw the possibilities in Frost’s second book, North of Boston. Critics had seen that collection as an interesting dead-end. I saw it as a road not taken to an alternative kind of modernism. It took me a year to start drafting a piece I called “The Mountain Climber” and several years to revise it into “The Room Upstairs.” It was my first long narrative poem.

DG: Let’s stay with narrative and Fitzgerald for a moment. In the same memoir, you write: “The surface of the poem, Fitzgerald's method implied, was the poem. No epic survived the welter of history unless both its language and story were unforgettable .... Only a few poets at a few fortunate points in history had met this challenge successfully. To understand the true value of these poems, Fitzgerald insisted, one not only needed to study the cultures and literary traditions that created them. One also needed to test them against life. The ultimate measure of Homer, Virgil, and Dante's greatness was that their poems taught one about life, and that life, in turn, illuminated them.”

How did Fitzgerald’s ideas shape your own aesthetic? Was his international perspective important for you?

Dana Gioia: One of the most important things I learned from both Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Bishop was that the surface of the poem was the poem. If the language itself didn’t communicate everything the reader needed, the poem would fail.

Both of those two poets had lived for long periods abroad—Fitzgerald in Italy, Bishop in Brazil. Both of them were fluent in other languages and had translated seriously. For Fitzgerald, translation became his life work. They both believed that poets needed to read broadly and not just in English.

As for judging a poem, I can’t see the purpose of a literary work, no matter how well written, that doesn’t ring true to life. It has always been the temptation of poets to spin out elegant fancies or empty bravado. Poetry must reconcile its sense of beauty with the world we actually inhabit.

DG: Your narrative poem, “Homecoming,” talks a great deal about life, but the violent ending inverts our understanding of it in a very dark way. The narrator kills his foster-mother in what initially feels like a clarifying moment of liberation. He quickly realizes, however, that the energy he felt “was just adrenaline—the phony high / that violence unleashes in your blood.” We understand that the speaker “had come home, and there was no escape,” which subverts Odysseus’s triumphant return home. What inspired the composition of this unusual poem? Was it an attempt to highlight how perverse our own society has become when compared to ancient civilizations like Greece?

Dana Gioia: “Homecoming” can surely be read as an indictment of contemporary society, but that wasn’t how I saw the poem. It was a tragic story that grew out of my own early life. There have been several murders in my family history—on both the Sicilian and Mexican sides. I even had a cousin who murdered his own brother. I began the poem with no idea where the story was going. I heard the speaker’s voice talking to me. I knew who he was but not what he would tell me.

“Homecoming” is the story of a young psychopath who eventually kills a number of people, including his foster mother. The tone is realistic, though often hallucinatory. The story grows slowly as the young boy develops, according to his own dark internal logic, into a sort of monster. What disturbs readers is not the violence or perversity of the poem but the intelligence of its narrator. That was the central premise of the poem—how could someone so intelligent and sensitive become so evil?

The way the poem grew and changed surprised me. I let the protagonist go where he needed to go. I first published it in a journal as “The Killer.” I then tore the poem apart, revising and expanding it to nearly twice the length as “The Homecoming.” It was only after I saw the first version in print that I understood how it needed to be fleshed out. I had no model for this kind of poem. I had to discover the style, the tone, and the narrative structure as I proceeded.

When my second book, The Gods of Winter, was in proof, my publisher, Scott Walker of Graywolf Press, wanted me to drop “The Homecoming.” He found it brutal and upsetting. I refused, but I decided to cut and sharpen it so that he could come to terms with its uncomfortable vision. Playwrights revise plays when they are in rehearsal. Why shouldn’t a poet do the same thing? The poem became stronger, and Scott agreed that it belonged in the otherwise tender book.

I actually revised the poem again for my selected volume, 99 Poems. I changed the title to “Homecoming” to distinguish it from the previous versions. So many people had written about the poem, I couldn’t change anything significant, but I sharpened a dozen or two lines. A poem this dark and unpleasant needed to be as perfect as possible.

DG: You mention working in isolation on your early narrative poems. Were other poets following a similar impulse? Did a new narrative tradition emerge in American poetry?

Dana Gioia: I didn’t know it at the time, but there were several other poets in my generation who shared this narrative impulse. Interestingly, they were mostly from the West. Robert McDowell and Mark Jarman had met at U.C. Santa Cruz. Like me, they were both from Los Angeles. Later they started an irreverent magazine called The Reaper which championed narrative. I did not know of the journal at the time, but I eventually met Robert and Mark. Meanwhile David Mason, who is from Washington state, began by writing short stories, a skill which helped make him the best narrative poet now active.

Each of us developed a slightly different solution to the challenge of poetic storytelling. All of us shared an admiration for the three modern American masters of narrative verse—E. A. Robinson, Robert Frost, and Robinson Jeffers.

DG: So you consider David Mason the most gifted narrative poet? What distinguishes him from other poets committed to exploring narrative?

Dana Gioia: Mason is unmatched in his talent and versatility. His stories and characters are compelling, and his language never loses its lyric impulse. He has also mastered different forms of poetic storytelling. He has written several remarkable short narrative poems, such as “Spooning,” as well as a compelling full-length poem, The Country I Remember. Narrated by a father and daughter, speaking a generation apart, it tells the story of a survivor of a Confederate prison who later makes his way West on the Oregon Trail. The poem is an astonishment. Finally, Mason has written an epic poem, Ludlow, about the tragic miners’ strike and massacre at Ludlow, Colorado in 1914. It says something about the imaginative power of these two poems that The Country I Remember was staged as a play, and Ludlow is being turned into an opera by composer Lori Laitman.

David Mason, WCU, 2013

DG: Your affinity for the work of Robinson Jeffers is well known. Born in the late nineteenth and writing in the early to mid-twentieth century, his work already anticipated much of the destruction, alienation, and apathy brought on by modern society. “The Purse-Seine” seems to be the most poignant and well known in this respect. What do you think of the political and environmental issues addressed in his work?

Dana Gioia: You can say that nearly everything Jeffers wrote is political in the sense that he rejected his age’s assumptions about society, culture, and the environment. He was, in some ways, the most political major poet of the Modernist era, but his views were never partisan in the narrow sense. He saw the horrific political events of his age from a global perspective—the destructive human race destroying themselves and the planet.

For that reason, it’s more accurate to consider Jeffers a prophetic rather than a political poet. A prophet tells people the uncomfortable truths they don’t want to hear.

DG: What are your favorite Jeffers poems, especially those that bring greater awareness of environmental and political issues?

Dana Gioia: I have a long list of poems by Jeffers I’d recommend. Let me suggest ten very different poems in addition to “The Purse -Seine,” which you mentioned. If readers don’t know these poems, they don’t know modern American poetry or California literature.

I would offer “Shine, Perishing Republic,” “Fawn’s Foster Mother,” “Hands,” “November Surf,” “Ave Caesar,” “Love the Wild Swan,” “Hurt Hawks,” “Rock and Hawk,” “Fire on the Hills,” and “Carmel Point.” I could go on. And we can’t forget his long poems, such as Cawdor, Roan Stallion or The Double-Axe. Jeffers would have considered the long poems his central works.

DG: There’s a photo of you and Morten Lauridsen, the great contemporary American composer, at Jeffers’s Tor House—his final residence in Carmel-by-the-Sea which he helped build with his own hands. Having been born in the Pacific Northwest and worked as a Forest Service firefighter, Lauridsen, too, like Jeffers, retains an affinity for the natural world. Can you talk a little bit about the special circumstances of this particular visit, what you talked about, and how the composer’s music has ultimately influenced your poetic sensibilities?

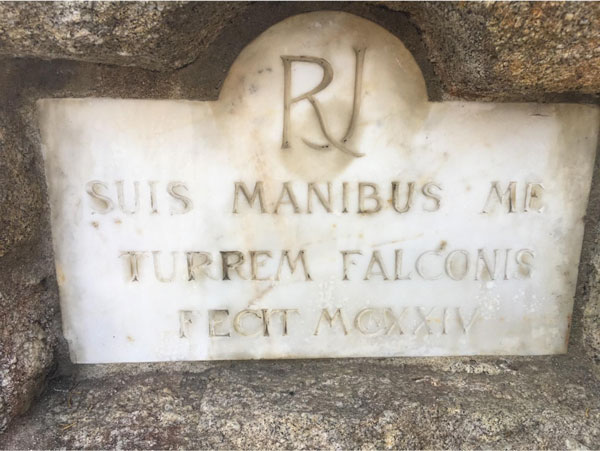

Dana Gioia: Jeffers is the greatest nature poet to have emerged in the American West. Even his home, Tor House, is a work of art. He built it, stone by stone, beam by beam, with his own hands on a promontory above the Pacific.

Latin Inscription: “With his own hands RJ built Hawk Tower for me.”

The composer Morton Lauridsen and I were the featured artists at a two-day choral festival in Santa Cruz. I wanted Lauridsen to see Tor House, and the staff made it available for us to visit, even though it was officially closed that day. We had the place to ourselves.

Lauridsen has spent much of his creative career living alone on a remote island in the San Juan archipelago in the Pacific Northwest. He bought and renovated an abandoned building overlooking the bay. Out of his sustained solitude, he created a music of intense beauty and spiritual force. His best music has a strange power. It fills an audience with awe and wonder. It brings many people to tears. The first time I ever heard his Lux Aeterna, which I knew nothing about before the concert, I understood I was hearing a masterpiece.

I knew that Tor House would have a profound effect on Lauridsen. He spent several hours there. Once we had seen every part of the place, he sat down at the old piano in the parlor, an instrument George Gershwin had once played during a visit. As the late afternoon light poured in from the Pacific, Lauridsen played the music that Una Jeffers had left on the piano sixty years earlier.

Mort Lauridsen Playing Piano at Tor House

Dana Gioia with Mort Lauridsen at Tor House

DG: Your work tends to be associated with New Formalism, a movement which emerged in the early eighties, promoting the revival of meter, rhyme, and narrative. At the same time, having collaborated with jazz musicians like Helen Sung on an album, you also have an affinity for a genre that seems to resist strict organization and structure. Two questions: Do you accept the New Formalism label, and if so, do you find that it contradicts, even in an interesting way, your relationship with jazz music?

Dana Gioia: The two parts of your question are more interrelated than you might think. I was drawn to poetic form not from any theory but because I love poetry for its sound. Poetry is speech raised to the level of music. I’ve tried to explore every way I knew of making words musical. A poem should be like a song, a kind of aural enchantment.

I have never liked the term “New Formalism,” but it has entered the critical vocabulary. It’s now listed in literary histories and books of literary terms. There isn’t much I can do about it. I accept it without enthusiasm. But anyone who knows my works understands that I work in both free and formal verse. What I’m after is lyrical energy in whatever way I find it.

Jazz is formal. It is a musical style in which there is a steady metrical beat which the soloist plays with, thereby creating a polyrhythm. The performers play with a melody and improvise over set chord changes. Jazz couldn’t improvise without that formal structure.

I do exactly the same thing in my metrical poems. I play with the beat. I contrast the underlying metrical rhythm with the speech rhythm. I’m always astonished that most critics don’t understand that fundamental fact of formal poetry. They only notice one half of the expressive structure.

DG: Let’s return to another narrative poem, “Style.” This long dramatic monologue addresses style in many of its varied connotations. The speaker Charlie proclaims: “Just look at me. Isn’t it obvious? / I have no style. I’m just a human blur.” Charlie’s friend, Tom, however, always “had the perfect sense for what was perfect.” The rich, handsome, and successful Tom becomes the subject of Charlie’s story. As we read the poem, Tom’s health problems conspire to destroy his perfect life, bringing him more or less level with Charlie. The lives in the poem reflect the sensibilities of jazz—they’re guided by unwritten rules, traditions, and expectations, and yet also totally governed by chance, luck, and improvisation. The business world that serves as the background to this poem harkens back to your life in New York.

Tell us about the creation of “Style.” Did moving to California affect the way you wrote about the world of New York business?

Dana Gioia: “Style” is a poem with such strong narrative thrust that the audience doesn’t notice how complicated it is. Only at the end does one realize how unreliable the narrator Charlie is and how complicated his relation is to Tom and Eden, the seemingly blessed couple. Those two characters are based on two people I knew in my New York years, though they weren’t a couple. Charlie is my own invention.

Poets don’t write about the business world—it is outside both their personal and imaginative experience. And yet it is the subject of great films, novels, and plays. I tried to get that part of the American experience into a very dark poem. “Style” captures the exhilaration, attraction, and precariousness of wealth as well as the destructive envy and fantasy it fosters. I saw that world as an outsider, and I was surprised by its fragility.

You are right that “Style” is a poem about New York where I spent twenty years, but it was written in California. The poem suddenly came to me when I heard about the death of the figure on which Tom is based—a man whose life seemed perfect in every respect. It’s about a man who was blessed in absolutely everything until the end. I don’t think I could have written it in New York. I needed the distance.

DG: In 2015 you became the California Poet Laureate. In a 2017 interview, published in Catamaran, you stated the desire, apart from the minimal official requirement of doing “just a few readings a year,” of wanting to accomplish something “more ambitious in order to reach beyond the urban cultural centers,” which are, as you said, “Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Berkeley.” Indeed, you made good on that promise and outlined a plan to visit all the state’s fifty-eight counties. At the time of the interview, you had already visited thirty-five, an impressive number.

Did you manage to complete this ambitious goal?

Dana Gioia: Yes, I eventually reached all 58 counties. It took nearly three years. In every county we arranged a public event that included local writers, musicians, and students.

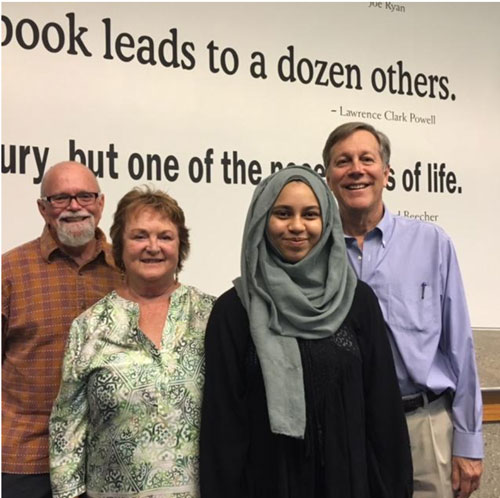

Dana Gioia, Orange County, 2016

I didn’t want the tour to be about me. I wanted it to be a celebration of local culture. In some small, rural counties I gave what might have been the first poetry reading ever.

Dana Gioia in Ventura County

DG: Do you have any particularly fond recollections from these travels across the state?

Dana Gioia: I have a thousand memories, large and small, about the trips. My wife drove with me to many of them. We are both native Californians, but we discovered places we had never seen before, especially in the Sierras. There are dozens of small counties that originated in the Gold Rush.

Dana Gioia at a Sacramento Poetry Society

It is a different world from coastal California. We organized 125 events, mostly in small towns or neighborhood libraries.

Dana Gioia in Toulumne County, 2016

We went to fascinating towns such as Mariposa, Downieville, Alturas, and Ferndale. I loved Crescent City on the edge of Pelican Bay and the Central Valley town of Turlock, full of Assyrians, Sikhs, and Vietnamese.

Dana Gioia and his fellow poets in Downieville (Population: 200)

My favorite single event was probably in agricultural Madera County where the library committee hosted a reading attended by people who worked on farms and ranches and a group of young men from the juvenile detention center. My BBC Radio producer had come out to make a “radio road movie” about the tour.

The Madera library ladies baked huge quantities of treats, which the teenage guys devoured. I took an extra break so that the guys could load up again. I got the most interesting and intelligent questions there, all from non-literary people. I read poems. A local high school student recited her Poetry Out Loud poems. My BBC producer, Julian May, who is a fine poet came up to recite, and I got one of the “cadets” of the detention center to perform a rap. A South American woman in the audience recited in Spanish, and a local Mexican welder showed his remarkable sculptures in the library lobby. It was an exciting event, and it gave the community a chance to understand itself.

DG: You’ve said that the “history of California poetry is mostly unwritten.” What do you mean by this?

Dana Gioia: There are many significant California writers whose lives and works have received little or no coverage. When I was editing the anthology, California Poetry: From the Gold Rush to the Present, with my co-editors Chryss Yost and Jack Hicks, we had trouble finding basic facts about many poets. But it’s a larger issue. California has been lax in recording and preserving its literary history. San Francisco has been well chronicled, but the rest of the state has not had much attention. A lot of that history is now unrecoverable. I wish California writers took their own traditions more seriously.

DG: For the past forty years you have championed the work of Weldon Kees, and kept his poetry and fiction from slipping into total obscurity. Can you talk about his influence on you, along with his importance to California poetry?

Dana Gioia: I consider Weldon Kees one of the major American poets of the twentieth century. Born in 1914, he is “mid-century” poet, a contemporary of Elizabeth Bishop, Theodore Roethke, and Gwendolyn Brooks. When I first came across his work back in 1976, I was astonished that he had been entirely forgotten. His poetry was out of print. His fiction had never been collected. He did not appear in anthologies. There was not a single substantial essay written on his work. I wanted to revive his reputation.

Kees is the darkest poet imaginable but also full of bitter humor—a writer who stares into the apocalypse and makes a graveyard joke. His poems are full of stylistic experimentation. He works in different forms—sestinas, sonnets, villanelles—as easily as free verse. His poems present the farrago of contemporary America without losing his imaginative control. When I first read him, I admired how he incorporated elements of popular culture—movies, jazz, advertising, radio, journalism—into his poems as naturally as high cultural literary elements. To him, it was all the detritus of a doomed society.

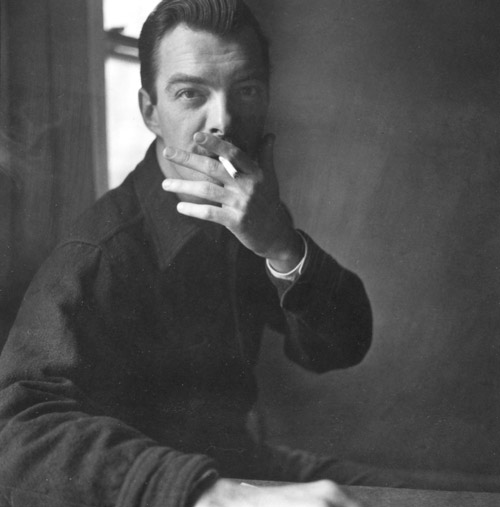

Weldon Kees

DG: What was his importance to California literature?

Dana Gioia: Kees came to California in 1950 and created a series of projects in poetry, film, painting, music, and theater. He was a true polymath. He started a literary cabaret, The Poets’ Follies and hosted an FM radio show on cinema. He played jazz, wrote songs, and shot experimental films. He painted as well as wrote poetry. Kees would have been at the center of San Francisco Renaissance had he not killed himself in 1955.

Dana Gioia at Mechanic's Institute Library, San Francisco

DG: Let’s return to supposed contradictions. Your personal background is a fascinating one—a Sicilian father and Mexican mother, Old and New World. Having myself visited Sicily, it’s certainly a place much like LA, in the sense that the island is a cultural melting pot: Greek, Roman, Spanish, French, Arab, and others, over many years, have come together to form a distinctive blend. And yet, the island is a place of contradicting, dialectical forces—people are both extremely open, gregarious, and welcoming, especially to guests; at the same time, they’re incredibly closed, suspicious, distant, especially to strangers.

You have stated that your “father was the only person in his family who had married a non-Sicilian.” In this respect, there’s even a proverb: “The love of a stranger is like water in a basket,” a sentiment which your parents fortunately proved wrong, but the contradictions nevertheless remain, and many Sicilian authors such as Giuseppe Borgese have commented on these Hegelian oddities: “Pride, and also baronial haughtiness, jealousy, impetus of love and hatred, constancy of loyalty and revenge, loyalty even in evil, generosity, if generosity can exist, even in crime; these are proverbial traits.” Is this really what it was like growing up, or did these traits slowly fade with time in the New World, and how did your mother’s New World perspective ultimately complement the household dynamic, along with your later development as not only a poet, but a California poet?

Dana Gioia: I’m the product of both the Sicilian world of my father and the Mexican background of my mother. I think of myself as a Latin. In both of those cultures, poverty does not keep someone from being proud and independent. I like Borgese’s notion of “baronial haughtiness.” Most relatives had great suffering in their lives. They took pride in their resilience. There was something old-world, indeed medieval about my family. Loyalty and toughness were two key virtues.

My background confuses some people, especially in the intellectual world. I don’t fit their stereotypes of Mexicans, Sicilians, and the poor. If you don’t fulfill their preconceptions, they don’t know what to make of you. I’m well educated and well read. I’m the first person in my family to go to college, but I learned as much in the public library as I did at Stanford and Harvard. Poor people aren’t dumb. I’ve moved among all American classes, and I’ve found intelligent and creative people at every level.

The other thing that confuses intellectuals and academics is that I still identify with the people who raised me. I have not tried to erase my cultural or class identity to become a generic American intellectual. I don’t see much value in an education that separates you from other people, especially your own flesh and blood.

DG: What are you working on at the moment?

Dana Gioia: I have two new books coming out. My new collection of poems, Meet Me at the Lighthouse, will appear in early 2023 from Graywolf. That publisher has been my home for nearly forty years—an amazing thing in the current literary world. I also have completed a new book of essays, Poetry as Enchantment, which will appear in two years from Paul Dry Books, in Philadelphia. Dry published my memoir, Studying with Miss Bishop, last year.

I have two other projects I want to complete—one in verse, the other in prose. I want to finish a book-length poem, called The Underworld. It is a narrative poem that moves in short lyric moments. I’m also writing a critical book titled Two Cursed Poets. It looks at the lives and works of Charles Baudelaire and Weldon Kees.

Who knows how much more time I have? I’m now seventy-one. I’m very conscious of how often older writers lose their edge. A well-known writer can coast on his or her past. I want to write at my best level. If I can finish those two projects with punch and panache, I will be satisfied. Anything more will be pure gravy.

Secret Garden

by Lara Alcantara-Lansberg

The Groves of Academe

|