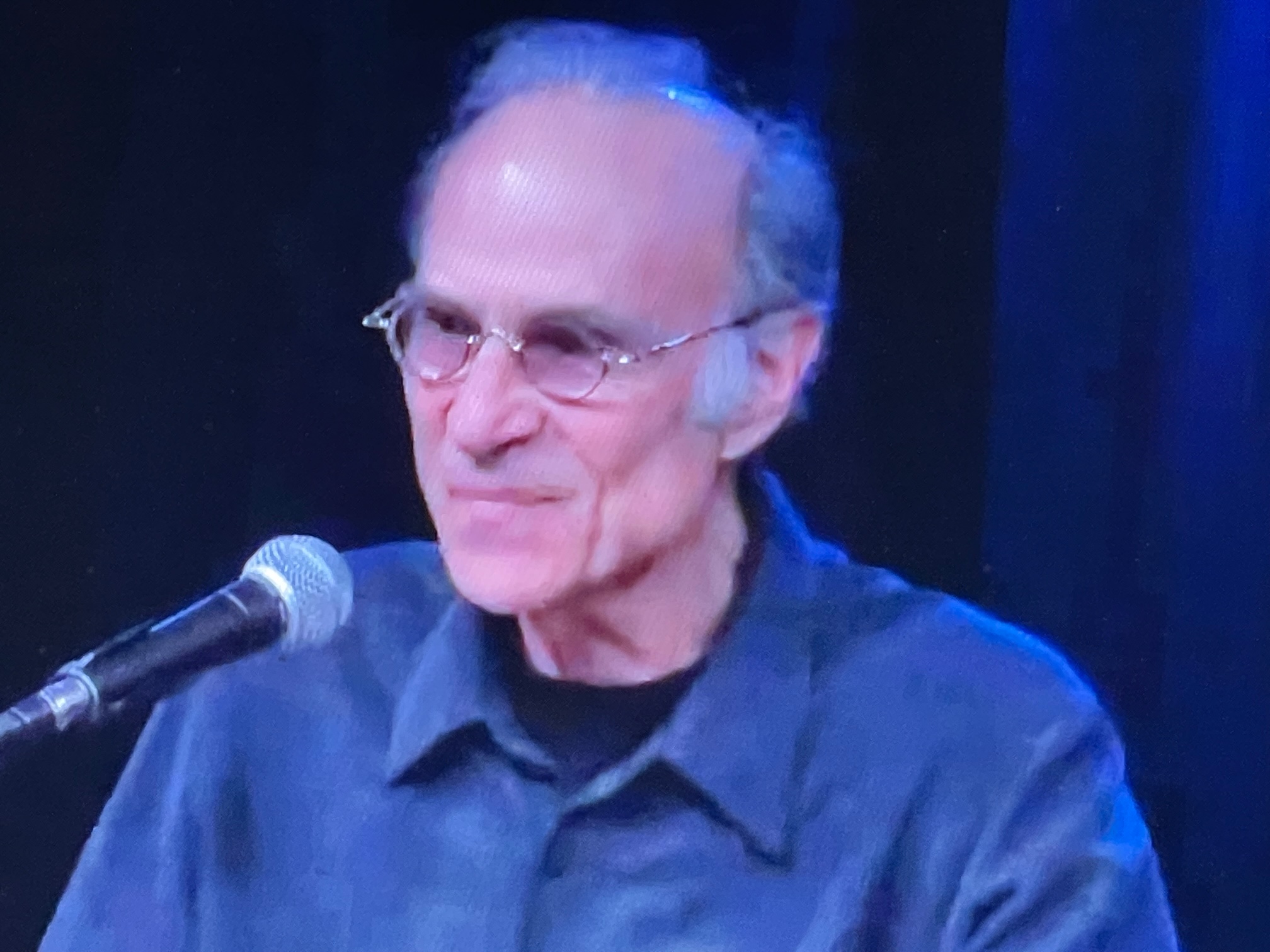

Stephen Kessler at the 2023 Santa Cruz County Artist of the Year Celebration

Stephen Kessler at the 2023 Santa Cruz County Artist of the Year Celebration

photo credit — SCCTV (Santa Cruz Community Television)

November 7th, 2023

Interlitq’s Californian Poets Interview Series:

Stephen Kessler, Poet, Translator, Journalist

interviewed by David Garyan

Stephen Kessler’s poems appear in Interlitq’s California Poets Feature

DG: Let’s begin with your translations, which include Luis Cernuda all the way to Jorge Luis Borges on the other side of the world. Apart from the vast geography, the writers you’ve translated also vary greatly in style. Can you talk about a project that you particularly enjoyed working on, along with one that posed significant challenges?

SK: Almost every translation project I’ve done has been a pleasure and a privilege and I’ve enjoyed them in different ways for different reasons, and each has presented its own significant challenges. Probably the book that was the most fun to do, thanks to the playful and irreverent attitude of the author toward his own collection of poems, is Julio Cortázar’s Save Twilight: Selected Poems, first published in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Pocket Poets Series in 1997, and reissued in an expanded edition about 20 years later after Lawrence had retired and Elaine Katzenberger was editor in chief. With many different kinds of poems and styles and voices he deployed over about 50 years, the book is completely unconventional and very funny in places, especially his cats’ editorial commentary in prose as they help him assemble the volume. The Argentine Cortázar, who spent his most productive years in Paris, is of course best known for his short fictions and his novel Hopscotch, but like Borges thought of himself primarily as a poet.

The Spaniard Vicente Aleixandre (Nobel laureate 1977), two of whose books I’ve translated—one early, one late in his career—is in the early work (La destrucción o el amor, Destruction or Love, 1933) very baroque in style, and in the later (Poemas de la consumación, Poems of Consummation, 1968) rather gnomic, so the Spanish in both cases, but especially in the later book, is unconventional and in places agrammatical. It’s tricky to be true to the original and not make it sound like a mistake in English. But since this stylistic trait recurs throughout the book, the reader should pick that up and realize the fidelity of what I’m doing, even if they can’t read the facing Spanish.

Cernuda (Spain), Borges (Argentina), and Neruda (Chile) are more straightforward and traditionally lyrical or conversational in style, but I think in part because all three are influenced by English or American poets, the syntax and language are easier for the reader to get on first reading. That doesn’t make translation any easier, but it facilitates understanding, so at least you (as a translator) know what you’re dealing with instead of being puzzled by unconventional usage, idioms or syntax.

DG: Let’s talk about the politics of translation: Do you have a different approach to the craft when tackling a writer like Borges (on the right of the political spectrum) as opposed to Neruda, for example, who was staunchly on the left?

SK: Borges was certainly conservative, and in the years of the Dirty War in Argentina (1976-83) was anti-chaos, but he was just as disgusted with the fascist generals as with the Marxist guerrillas. In his poetry he romanticizes the physical courage of both his military ancestors and the knife-fighting hoodlums of old Buenos Aires, but none of that has anything to do with politics. It has more to do with the reveries of a blind, bookish, physically limited man and his admiration for the “manliness” of others.

Neruda was converted to communism largely on the basis of his experience in Spain in the mid-1930s and his friendships with the poets of the Generation of 1927 (García Lorca, Aleixandre, Cernuda, Guillén, Salinas, and others) and the invasion by Franco and his fascist forces to overthrow the Spanish Republic in 1936. Until then, Neruda was a romantic and a surrealist. His famous poem “Explico algunas cosas” explains his conversion to political engagement. Unfortunately, in my opinion, Neruda is at his worst and most boringly rhetorical when he puts on his Voice of the People persona and speaks as if he’s preaching to a stadium full of workers. That said, his epic history of the Americas, Canto general, is one of the greatest works of its genre, for sure; I’ve done one of the many translations of Alturas de Machu Picchu from that work, which is a very powerful—and all but impossible to translate, which is why there are so many versions in English—long poem in homage to the anonymous (enslaved) workers who built that mysterious city.

As for differences in approach to translating such different kinds of voices, I consider myself a proponent of the Method acting school of translation. I try to find in the deepest part of myself, no matter how different my experience or perspective is from the author’s, an identification with what they’re doing (saying, feeling, thinking) and the tone and feel of their speaking voice, and try to inhabit that persona and speak it as I think it would sound if it had been written originally in English.

In terms of “craft,” I bring the same skills and tools to every translation—like a musician so deeply practiced in the technical aspects of his instrument that he can improvise spontaneously without thinking—which are the same ones I use in my original poems: imagination, familiarity with certain traditions, knowledge of prosody, an ear for the sound of the Spanish and how that could be echoed in English, attunement to local or regional idioms, and a certain flexibility and confidence in my instincts developed over decades of practice. More important for me than “craft” is that you must understand what you’re translating before you take it too literally. Even native speakers sometimes don’t understand poetry—and sometimes even the poet is composing more for sound or image than “literal” meaning. (There is some disagreement among translators as to whether there’s even such a thing as a literal translation.) But you have an ethical obligation to be as true as possible to the original. So those are some of the elements in play as I approach any poet regardless of their politics or personality.

DG: You came to Santa Cruz in the early ‘70s and since then have contributed greatly to the literary community. Can you speak about how SC influenced your writing, how the city itself has changed, along with the benefits of working outside the traditional LA/SF paradigm?

SK: I first arrived in Santa Cruz in 1968 on a four-year Regents Fellowship to UCSC at the dawn of their doctoral program in literature, but it didn’t take long for me to realize the academy was not where I wanted to be, and a psychic crisis at the end of 1969 (fictionalized in my novel, The Mental Traveler) was the deciding event that ended my career in graduate school. After a year in Southern California recovering from my psychotic break in therapy, I returned to Santa Cruz and in 1972 started writing for what was then called the underground press, which evolved into the alternative press, and locally was a series of weekly community newspapers that I became more and more involved in as a writer, editor, and eventually (1986) publisher of my own independent weekly called The Sun, which was put out of business by the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake.

In the early ‘70s I was one among several young poets just starting out, and it was such a tight community, largely wrangled together by Morton Marcus, who taught at Cabrillo College and was the most widely published poet in town, that for a few years many friendships were formed as we egged each other on, sending poems back and forth in the mail and reading in each other’s homes and in one series or another that Mort organized at local restaurants and cafes. This was a formative time for me; I was reading all kinds of different things and beginning to translate, and being part of a community of poets apart from any academic setting was healthy for my development as a writer after grad school. I also brought my training as a critic to bear on my journalism, and so was an active supporter of a literary culture that, in those years, was not way out on the margins; it felt like poetry had a place of value as part of the cultural life of the city and region.

The journalism, especially in the opinion columns I started writing then, was a way of infiltrating a nonliterary medium with a poet’s sensibility, and in some ways the essays I was writing for the press were my most “experimental” form. I also wrote features of various kinds, cultural and political, that made me feel relevant to a range of readers who’d never pick up a book of poems or a little magazine, and as the poetry world felt more and more like a small subculture where so little was at stake that the people inside it had a distorted notion of their own importance, I was more and more engaged with the role of the local press in addressing what mattered in the real world. So I’ve been doing that, in one form or another, not just in Santa Cruz but when I lived on the Mendocino Coast in the ‘90s, ever since. For the last 10 years or so I’ve been writing a weekly opinion column for the daily Santa Cruz Sentinel, a legacy paper started by a local family in the mid-1800s and now owned by a hedge fund in New York. I am still a generalist and write about whatever’s on my mind ranging from personal history to cultural criticism to local and national and international affairs. I feel it’s the best use of my writing skills as a contributor to the community.

I never thought much about “the LA/SF paradigm” except that I was connected with poetry networks in both places and gave readings and published in various magazines north and south. I think of myself as a California poet with ties to both LA and San Francisco, as well as in the North Bay and on the North and Central coasts. But in the intimacy of a smaller town like Santa Cruz I felt I could make much more of a difference, especially as a journalist, and I think I have. This year the county arts commission named me their Artist of the Year for my accomplishments and contributions over the last 50 years.

As for how the town has changed through the past half century: in a word, immensely. It’s now much more like a little city with a big arts scene with countless artists and musicians and scores or maybe hundreds of published poets and groups and networks, and in terms of population and development, it’s exploded. UCSC has had a lot to do with this, and the Silicon Valley-fueled real estate boom since the ‘90s. But this is a subject much too big to discuss in an interview like this.

DG: Let’s turn towards your novel, The Mental Traveler, an homage to the great Blake’s vision of a cyclical history. At the same time, the main character’s name is curiously Stephen K. and seems to be based on your early experiences. A 22-year old literature graduate student falls into a crisis, going from one psychiatric institution to the other, until, paradoxically, literature provides a revelation, and it’s Robert Bly’s poem “Anarchists Fainting.” Now, the young generation seems more lost than ever: COVID, economic instability, wars. What are some poems you turn to for guidance today?

SK: Stephen K. is caught up in the contradictions between his vocation as a poet and the demands of a respectable academic career in the midst of the tumultuous social, cultural, and political upheavals of that historical moment. He has a flash of insight after six months in madhouses when he reads “Anarchists Fainting” in Harper’s (later published in Bly’s book Sleepers Joining Hands as “Condition of the Working Classes: 1970”) which, in his heightened awareness, sometimes called paranoia, he thinks is about him. That is in the final chapter after many disorienting and picaresque adventures leading up to a breakthrough realization. I’ll leave it at that, but the book is a story of artistic initiation in a supercharged historical context—which at the time, subjectively, felt fraught in much the same way that today does—but today is far worse, with many and far more serious crises than could have been imagined then.

But I didn’t then and don’t now look to any particular poems for guidance. I read poetry for pleasure and inspiration, not instruction. Poetry at its best can illuminate reality and show us things we never saw that way before, and for me that’s the most we can ask of it. It’s really hard to write good, original poems, whatever the theme or subject—love, nature, justice, friendship, identity, consciousness, war, politics, etc.—and a freshly imagined poem of any kind can be helpful in getting me through the day. But I do not have a utilitarian concept of poetry, or a Garrison Keilloresque notion that it’s necessarily good for us as readers, like eating our vegetables. There’s so much poetry out there now, competent but generic, thanks to the creative writing industry, and not that much of it is of interest to me. I’m still reading things from centuries past that I should’ve got around to sooner, like the ancient Greek and Roman epigrammists, or the ancient Persians or Chinese. I think everyone individually has to find the poems that speak to them and give them what they need. For me poetry has always been about an intimate connection between what’s on the page and the reader, and like any relationship, it’s different for different people at different times and under different conditions.

I enjoy reading poems to an audience, to hear what they sound like out loud, but my primal and most intense connection with poetry originally was reading it on the page, as in the scene with the Bly poem in The Mental Traveler.

DG: One of the last emails you received from the late Jack Hirschman was “Caro, Stephen, Understood”—in reply to your preference not to get involved in his effort to organize politically-related readings and events. Before his death, he was due to fly to Italy, where as you write, “he was far more famous than in the States.” Those who knew him know they need him more than ever now. Yet, there are still those who’ve yet to discover his work. Can you speak about your favorite pieces of his, and how his work affected your own development?

SK: Jack’s magnum opus is the three-volume 3,000+ page The Arcanes—his Cantos, or anti-Cantos, as he hated Pound—published in Italy and probably hard to find in the States. Except for a couple of books from City Lights, the rest of his 100+ books of poems and translations were issued by very small presses—though I imagine some of his work can be found online. But as I wrote in my postmortem appreciation of him, published online in the LA Review of Books, the most important way he inspired, moved, and encouraged people was by his generous presence as a completely unique personality and organizer of a poetry community, mainly in San Francisco. I declined his call to organize events with a political slant because I don’t have time and I don’t think it does much good except to make the already convinced feel good about themselves for opposing capitalism, war, or whatever. But Jack was an agitator. His “Stalinist” politics were kind of a self-caricature, as far as I’m concerned—he was a romantic utopian more than a real communist—and his politics made him seem more ridiculous to some people than he actually was. So if anyone wants to discover his work, I wish them the best. But it’s less his prodigious writings than his person that I valued, first as a teacher at UCLA in 1966, and later in San Francisco as a friend and as an example of someone totally committed to poetry. We had a lot of disagreements about what kind of poetry is of greatest value, or is any good.

DG: Let’s talk about your most recent collection, Last Call (2021). The 169-page collection is your biggest to date, covering a wide range of topics. The noted poet Joseph Stroud, said the following: “There is a wonderful term in Italian—Sprezzatura—which is the art of making the difficult appear easy, a kind of grace that cloaks a deep mastery of craft. I find this quality, this Sprezzatura, everywhere in Stephen Kessler’s work.” And yet, sprezzatura does not at all suggest a lack of effort—it merely implies the appearance of a lack of effort when the presentation takes place. Thus, in truth, to produce this aforementioned “appearance,” sprezzatura actually requires a great deal of blood, sweat, and tears behind the scenes. Can you talk about some of the most crucial aspects, with regard to this project, from start to finish?

SK: That was a very generous endorsement of my work by my old friend Joe Stroud, whom I met more than 50 years ago when we both came to Santa Cruz, and who I consider another example of someone devoted, in a completely different way from Hirschman, to the ethos and practice of poetry, and certainly among the most accomplished poets in this region (though he only spends part of the year here). I think of Joe as a “pure poet,” committed exclusively to poetry in a way that I couldn’t be, which is why I’ve diversified my practice for all this time. But if my writing has “sprezzatura,” I think it’s because I’ve been practicing so long—again, like a veteran jazz musician—that it comes fairly easily to me at this stage of my journey, and I’m not trying to please or impress anyone else, so I’m free to trust my own voice (as another teacher of mine, Robert Duncan, counseled) and let it rip, intuitively trusting my technical skills to make the right words land in the right places. It’s not as if I don’t revise and refine, but I like to improvise very spontaneously and then go back and fix whatever needs improvement. Some poems make it and some don’t, but I’m not after perfection and can accept failure when they don’t work.

I also think of myself in the lyrical vernacular tradition ranging from Wordsworth through Whitman to Williams, O’Hara, and Bukowski, writing the way I speak, or would like to speak if I could speak that precisely and musically all the time.

Except for Where Was I?, my book of prose poems about place, or places, I don’t really think of my books of poems as projects. I write poems as they come to me, one at a time, in various moods, modes, styles and forms—I consider myself a heteroformalist—and at some point, after a few years, usually corresponding to some turning point in my life, I realize I have the makings of a book and then try to put it together in a way that the poems seem to organize themselves. Sometimes by theme, sometimes as a journey, sometimes in roughly chronological order, sometimes in what feels like a natural progression from one poem to another. Last Call was written between 2017, when my marriage broke up, and 2021, just after the Covid lockdowns. It’s organized by theme or mood in seven sections and it covers a lot of ground in terms of style, tone, form, and feeling. It’s a bigger book than most of my previous collections just because I was writing more, or more poems worth saving, and my publisher, Joe Phillips of Black Widow Press, is “not afraid of big books,” as he told me about my Cernuda volume Forbidden Pleasures, so I included everything I thought could stand up with time. And so far, when I look at those poems, I think I made the right call in its composition; I think they hold up pretty well.

DG: Los Angeles was the city that, as you’ve said, made you a poet. How has the city changed since you were growing up, and is there perhaps anything you miss about it that’s still there?

SK: The city seems vaster than ever, with more freeways and more traffic, and the spread of suburbs, and the usual development and redevelopment. And Covid shut down a few of my favorite things, like the big Landmark multiplex art house cinema at Pico and Westwood. But no, I don’t miss LA at all, especially the traffic and the freeways, and when I visit there from time to time—mostly to see friends and family, or more recently to attend funerals—I’m always happy to return home to little Mediterranean Santa Cruz, though it has changed a lot, too. My essay “The Architecture of Memory,” published in LARB, is mostly about places that no longer exist, or not in the form I knew them in the 1950s and ‘60s. The great LA poet Wanda Coleman, who died about 10 years ago, was a good friend and an inspiration, and I miss her a lot. There are still parts of LA I enjoy visiting, certain neighborhoods or parks or restaurants or movie theaters, but I’m really glad I got out of there when I did.

DG: Let’s return to translation, but from a different perspective. Is there a language you would love to have your work translated into?

SK: I would be honored to be translated into any language a competent translator felt I deserved to be published in. Naturally because of my connection with Spanish, Spain and Latin America would be among my top preferences. But my books in the States sell no more than a few hundred copies, mostly in California, so I don’t anticipate the market for what I do would be any larger elsewhere. My translations are much more successful, in terms of sales, in part because I’ve chosen or been chosen to work with major poets who’ve proved their staying power, and partly because my translations happen to represent them very well, and have won numerous awards, which has also helped raise their profile.

DG: What are you reading and/or working on at the moment?

SK: Lately I spend more hours reading The New York Times than anything else, in part because I want to know what’s going on in the world—which of course relates to my job as a newspaper columnist—and partly because it’s such a great newspaper and I admire so many of the writers, the editing, the page design (I read it on paper), the headlines, the features, the reporting, the photographs and illustrations, the analysis, the editorials, the letters. It’s like a daily anthology of great stories and excellent writing. Back around 1969 the critic Seymour Krim published an essay in Evergreen Review, “The Newspaper as Literature,” a kind of manifesto that argued for literary writers to engage with the historical moment—which New Journalists like Norman Mailer and Joan Didion and others were doing—by infiltrating the nonliterary press. Jimmy Breslin in New York (with the Daily News) was a model for Krim of a traditional reporter writing things of both immediate and lasting value. And that has turned out to be central to my own practice, publishing my essays in newspapers as well as more strictly literary venues. So I am, for better or worse, addicted to the Times.

Usually before bed, as an antidote to all the bad news, I pick up a book from the pile next to my chair and read a few pages. Lately I’ve been reading Didion (nonfiction), Ben Lerner (fiction), Fernando Pessoa, Mahmoud Darwish, Hafiz (in a new translation by my old friend Gary Gach), Michel Houellebecq, Louise Glück, and somewhat randomly sampled other poets in my library. I try to keep up with books by friends who send them to me, but I don’t follow much contemporary poetry or fiction. I very much enjoyed Sarah Bakewell’s life of Montaigne, How to Live, one of the few books of more than 300 pages I’ve read in a while.

Unless something extraordinary comes to my attention and my inspiration, I feel I’ve pretty much retired as a translator, having fulfilled my destiny with the three Cernuda books: Written in Water, Desolation of the Chimera, and Forbidden Pleasures. He’s one of the greatest poets in Spanish, and I think I’ve done him justice and performed a valuable service, even if the number of readers in English is limited, for now.

As for what I’m working on, the essays for the column, constantly, which range all over whatever I’m thinking about, and I have some 40 new poems since Last Call that may eventually amount to part of a book, but I don’t expect that for at least another two or three years. At some point I’ll probably try to put together a Selected Poems, but I figure I’ll know when to do that, if I live long enough.

Author Bio:

Stephen Kessler is the author of a dozen books of original poetry, sixteen books of literary translation, three collections of essays, and a novel, The Mental Traveler (Greenhouse Review Press). He is the editor and principal translator of The Sonnets by Jorge Luis Borges (Penguin Classics) and was for sixteen years (1999-2014) the editor of The Redwood Coast Review. The poems here are from his most recent book, Last Call (Black Widow Press, 2021). A longtime resident of Santa Cruz, he writes a weekly op-ed column in the Santa Cruz Sentinel. www.stephenkessler.com

Daniel Yaryan

Daniel Yaryan

Terry Ehret

Terry Ehret Doreen Stock

Doreen Stock